The rather presumptious title assumes the laws and fundamental constants of physics are the same everywhere (they may not be). With this constraint (and without yet defining what is meant by strongest), consider the three molecules: Read the rest of this entry »

The strongest bond in the universe!

October 24th, 2010Hypervalency: Third time lucky?

October 23rd, 2010One approach to reporting science which is perhaps better suited to the medium of a blog than a conventional journal article is the opportunity to follow ideas in unexpected, even unconventional directions. Thus my third attempt, like a dog worrying a bone, to explore hypervalency. I have, somewhat to my surprise, found myself contemplating the two molecules I8 and At8. Perhaps it might be better to write them as I(I)7 and At(At)7. This makes it easier to relate both to the known molecule I(F)7. What led to these (allotropes) of the halogens? Well, as I noted before, hypervalency is a concept rooted in covalency, albeit an excess of it! And bonds with the same atom at each end are less likely to be accused of ionicity. I earlier suggested that the nicely covalent IH7 was not hypervalent, with all the electrons which might contribute to hypervalency actually to be found in the H…H regions. The next candidate, I(CN)7 ultimately proved a little too ionic for comfort. So we arrive at II7. At the D5h geometry, it proves not to be a minimum, but a (degenerate) transition state for reductive elimination of I2 (I note parabolically that the 2010 Nobel prize for chemistry was awarded for reactions which involve similar reductive elimination of Pd and other metals to form covalent C-C bonds). Thus I8 is useful only as a thought experiment molecule, and not a species that could actually be made.

And now for something completely different: The art of molecular sculpture.

October 17th, 2010Chemistry as the inspiration for art! The inspiration was the previous post. As for whether its art, you decide for yourself. Click on each thumbnail for a molecular sculpture (the medium being electrons!). Read the rest of this entry »

Hypervalency: I(CN)7 is not hypervalent!

October 17th, 2010In the last post, IH7 was examined to see if it might exhibit true hypervalency. The iodine, despite its high coordination, turned out not to be hypervalent, with its (s/p) valence shell not exceeding eight electrons (and its d-shell still with 10, and the 6s/6p shells largely unoccupied). Instead, the 14 valence electrons (7 from H, 7 from iodine) fled to the H…H regions. Well, perhaps H is special in its ability to absorb electrons into the H…H regions. So how about I(CN)7? (the species has not hitherto been reported in the literature according to CAS). The cyano group is often described as a pseudohalide, but the advantage of its use here is that it is about the same electronegativity as I itself, and hence the I-C bond is more likely to be covalent (than for example an I-F bond). As noted in the earlier blog, if the potentially hypervalent atom is very ionic, it can be difficult to know whether the electrons are truly associated with that atom, or whether they are in fact in lone pairs associated with the other electronegative atom (e.g. F). It is also important to avoid large substituents, otherwise steric interactions will cause problems around the equator.

Hypervalency: Is it real?

October 16th, 2010The Wikipedia page on hypervalent compounds reveals that the concept is almost as old as that of normally valent compounds. The definition there, is “a molecule that contains one or more main group elements formally bearing more than eight electrons in their valence shells” (although it could equally apply to e.g. transition elements that would contain e.g. more than 18 electrons in their valence shell). The most extreme example would perhaps be of iodine (or perhaps xenon). The normal valency of iodine is one (to formally complete the octet in the valence shell) but of course compounds such as IF7 imply the valency might reach 7 (and by implication that the octet of electrons expands to 14). So what of IF7? Well, there is a problem due to the high electronegativity of the fluorine. One could argue that the bonds in this molecule are ionic, and hence that the valence electrons really reside in lone pairs on the F. Thus the apparently hypervalent PF5 could be written PF4+…F–, in which case the P is not really hypervalent after all. We need a compound with un-arguably covalent bonds. Well, what about IH7? One might probably still argue about ionicity (for example H+…IH6–) but that puts electrons on I and not H, and hence does not change any hypervalency on the iodine. Surely, if hypervalency is a real phenomenon, it should manifest in IH7?

Secrets of a university admissions interviewer

September 19th, 2010Many university chemistry departments, and mine is no exception, like to invite applicants to our courses to show them around. Part of the activities on the day is an “interview” in which the candidate is given a chance to shine. Over the years, I have evolved questions about chemistry which can form the basis of discussion, and I thought I would share one such question here. It starts by my drawing on the blackboard (yes, I really still use one!) the following molecular structure.

Solid carbon dioxide: hexacoordinate carbon?

September 17th, 2010Carbon dioxide is much in the news, not least because its atmospheric concentration is on the increase. How to sequester it and save the planet is a hot topic. Here I ponder its solid state structure, as a hint to its possible reactivity, and hence perhaps for clues as to how it might be captured. The structure was determined (DOI 10.1103/PhysRevB.65.104103) as shown below.

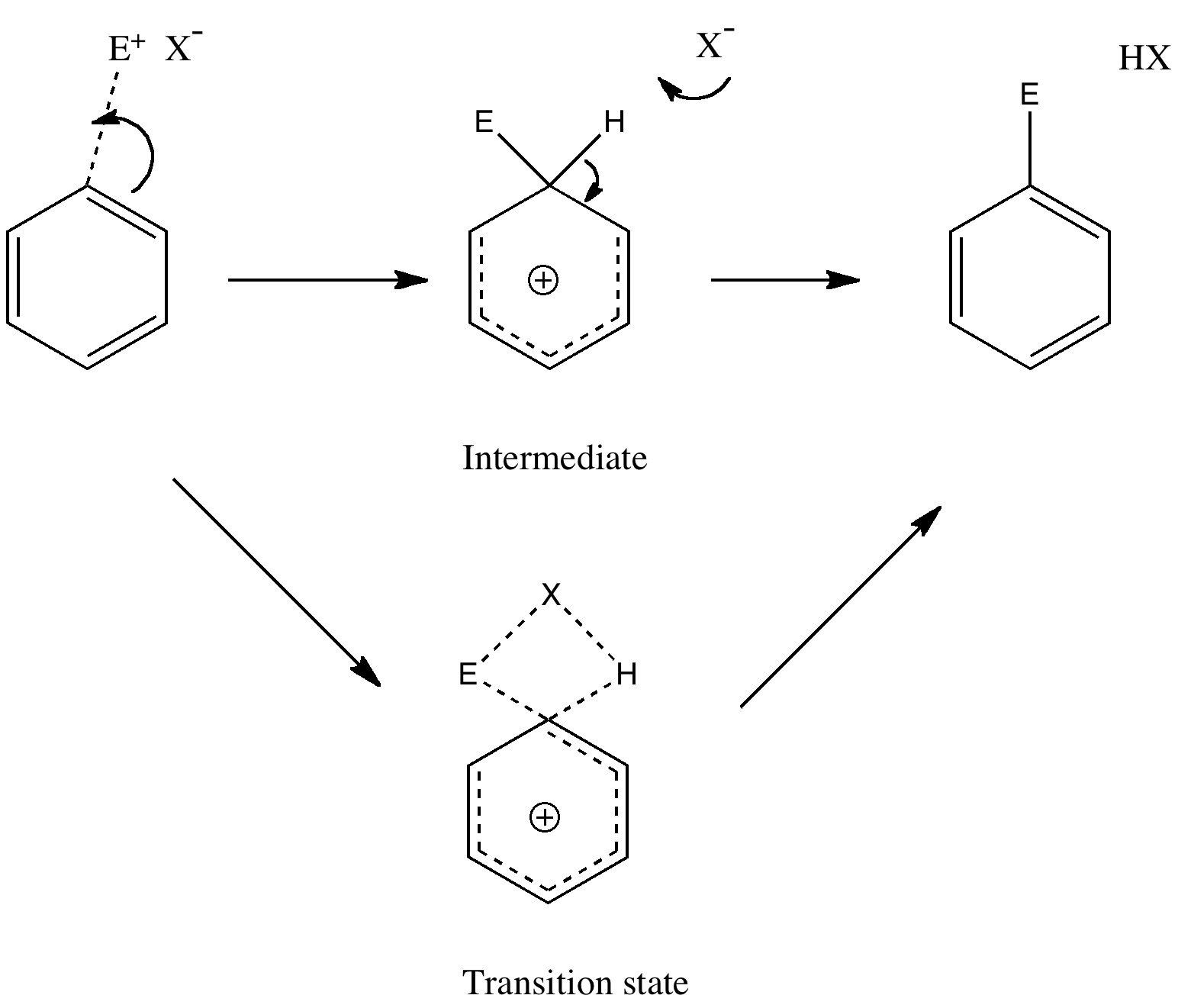

The oldest reaction mechanism: updated!

September 14th, 2010Unravelling reaction mechanisms is thought to be a 20th century phenomenon, coincident more or less with the development of electronic theories of chemistry. Hence electronic arrow pushing as a term. But here I argue that the true origin of this immensely powerful technique in chemistry goes back to the 19th century. In 1890, Henry Armstrong proposed what amounts to close to the modern mechanism for the process we now know as aromatic electrophilic substitution [cite]10.1039/PL8900600095[/cite]. Beyond doubt, he invented what is now known as the Wheland Intermediate (about 50 years before Wheland wrote about it, and hence I argue here it should really be called the Armstrong/Wheland intermediate). This is illustrated (in modern style) along the top row of the diagram.