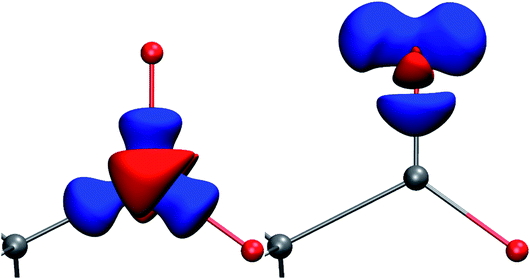

X-ray crystallography is the technique of using the diffraction of x-rays by the electrons in a molecule to determine the positions of all the atoms in that molecule. Quantum theory teaches us that the electrons are to be found in shells around the atomic nuclei. There are two broad types, the outermost shell (also called the valence shell) and all the inner or core shells. The density of the core electrons is much higher (more compact) than the more diffuse valence shell for all but the hydrogen atom, which only has valence electrons. How does this relate to x-ray diffraction by electrons? Well, core electrons, because of their relative compactness, diffract X-rays more strongly than the valence electrons. This compactness of the core also means that its electron density distribution can be well (but not exactly) approximated by a sphere, with the nucleus at the centre of that sphere. And from this it follows that the density for each atom can be treated independently, the so-called IAM or independent atom model. For example all the carbon atoms in a molecule are approximated as having the same value for the electron density of their core shell. But the IAM approximation is much less good for hydrogen atoms, especially when they are attached to very polar atoms (Li, O, F, etc) and even atoms such as carbon or oxygen have noticeable deviations as illustrated in figure 1 below. [1]

Figure 1 from [1] with caption: Deformation Hirshfeld densities for the carbon (left) and oxygen (right) atoms in the carboxylate group of Gly-l-Ala, i.e. difference between the spherical atomic electron density used in the IAM and the non-spherical Hirshfeld atom density used in Hirshfeld atom refinement=HAR (IAM minus HAR). Red = negative, blue = positive. Isovalue = 0.17 eÅ−3.‡

X-ray crystallography is all about matching the electron density map of a model structure with the electron density map derived from the diffraction data. In “conventional” X-ray crystallography – i.e. that used by most crystallographers – the electron density map of the model is calculated using the IAM approach, where no consideration is given to any distortion of the electron density distribution caused by things like bonds – each atom is treated independently (hence the name). This method especially struggles with hydrogens and hence the inferred position of the hydrogen nucleus at the centre of an assumed spherical distribution is often difficult to obtain accurately. Enter quantum crystallography, whereby a model of the electron density distribution in a molecule can be calculated by solving the Schrodinger equation, nowadays to a very reasonable approximation in a reasonable time (minutes) using so-called density functional theory, or DFT. The resulting electron density map for the model structure might be expected to more closely match reality than the IAM approach. Most obviously affected by this change is the handling of hydrogen atoms. If one considers a C–H bond from an sp3 carbon atom, using an IAM approach the hydrogen atom (i.e. its nucleus or proton) would be placed at the centre of maximum electron density, in the full knowledge that this is not actually where the hydrogen atom nucleus itself is. The direction of the C–H vector would be correct, but the distance would be too short. In the quantum crystallography approach, the positions of e.g. hydrogen atom nuclei are not exactly coincident with the electron density maxima, amounting in effect to non-spherical atoms, thus avoiding the systematic errors seen in the IAM approach. Smaller, but possibly still significant such errors might be expected for e.g. the 2nd row elements and beyond.

Getting reliable hydrogen atom positions has previously required a neutron diffraction study, which is difficult, expensive and time consuming. So the idea of using the non-spherical DFT densities rather than the spherical IAM approach to build a model using X-ray diffraction data is very appealing. But does it work? To test this, we decided to go back to some previously published structures that were handled using the IAM approach, and re-refining them using quantum crystallography. We do not have the corresponding neutron studies to check the answers against, but we can still see how well the structures themselves refine and what new problems this approach might throw up.

Method

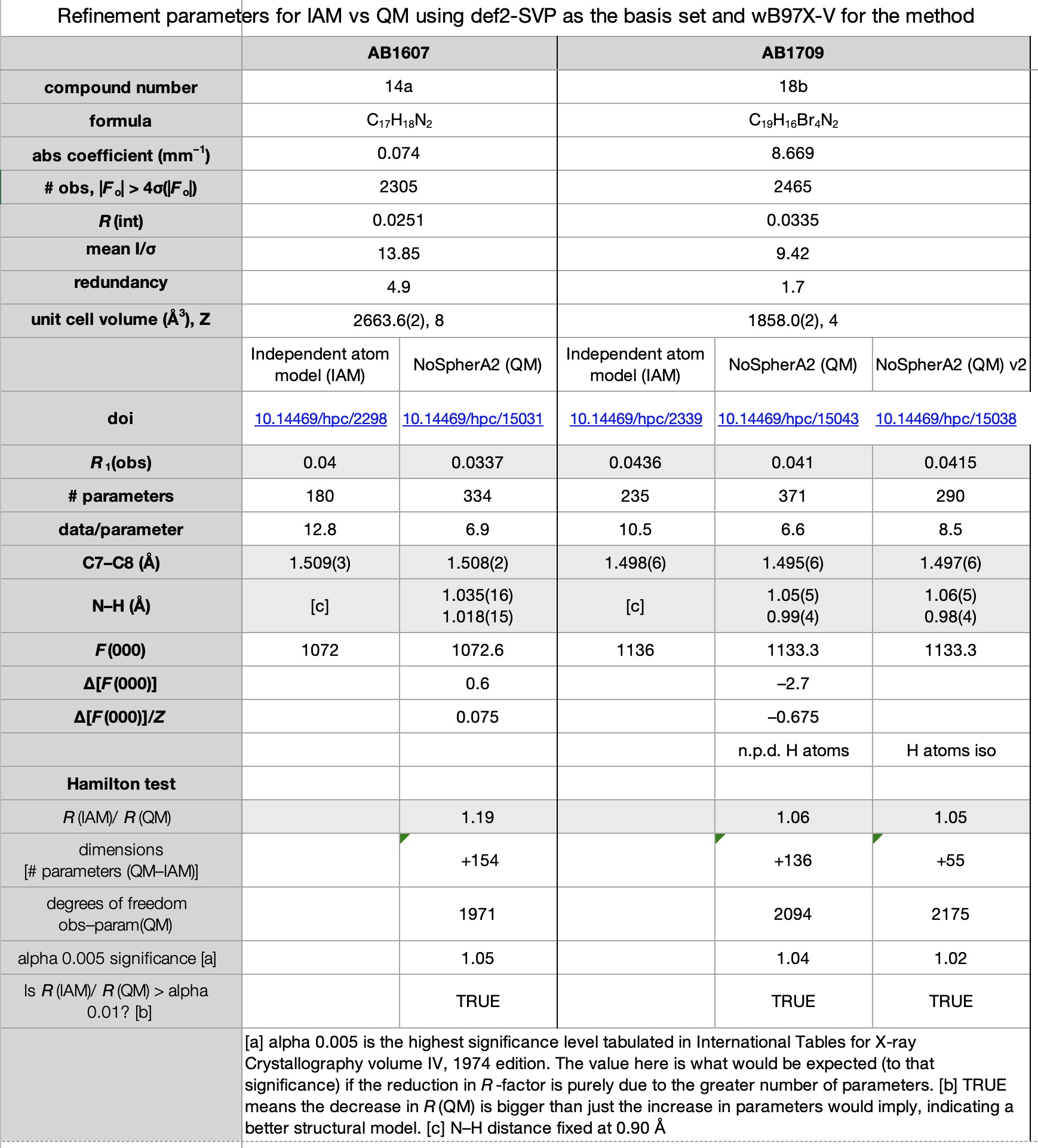

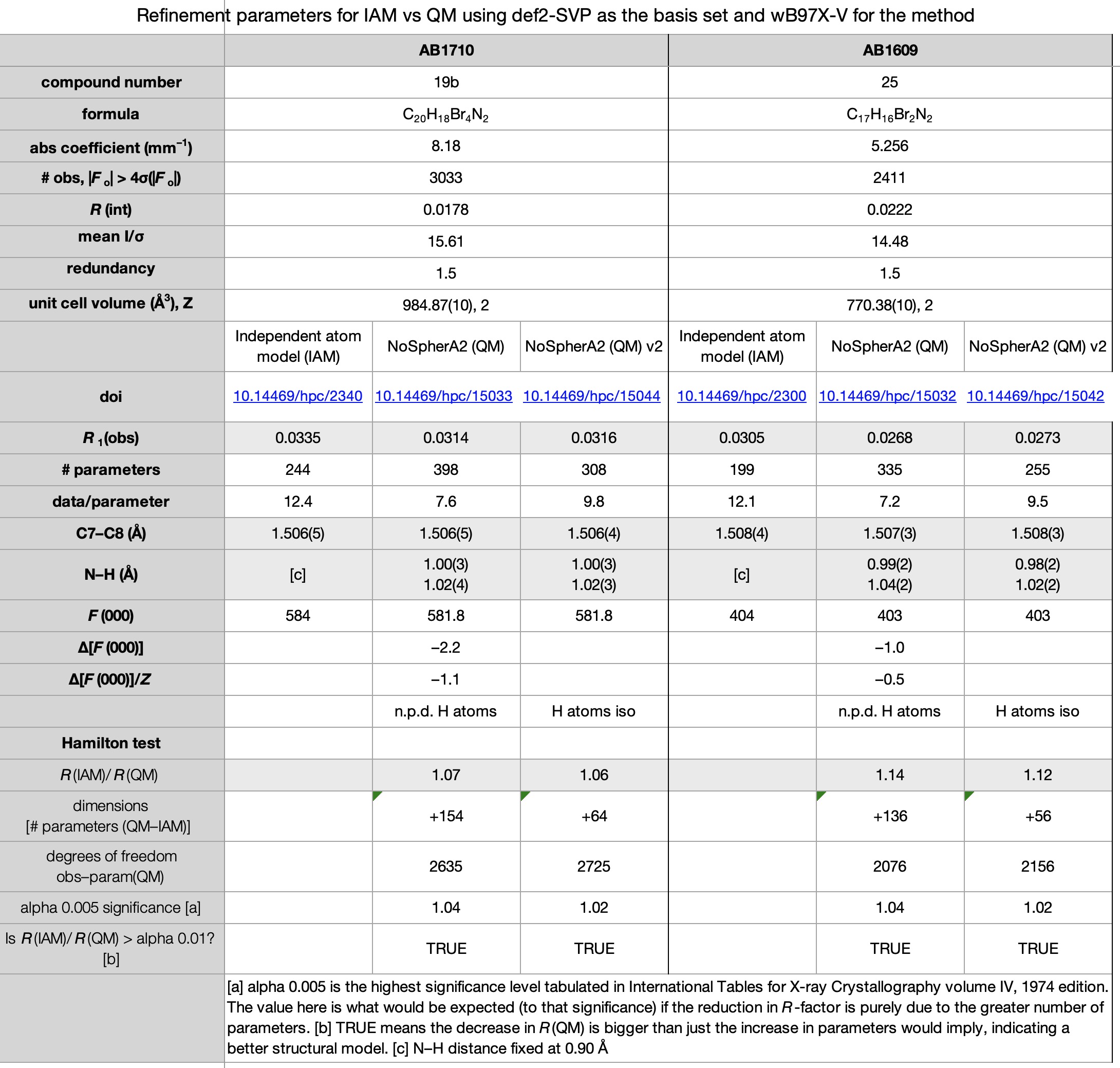

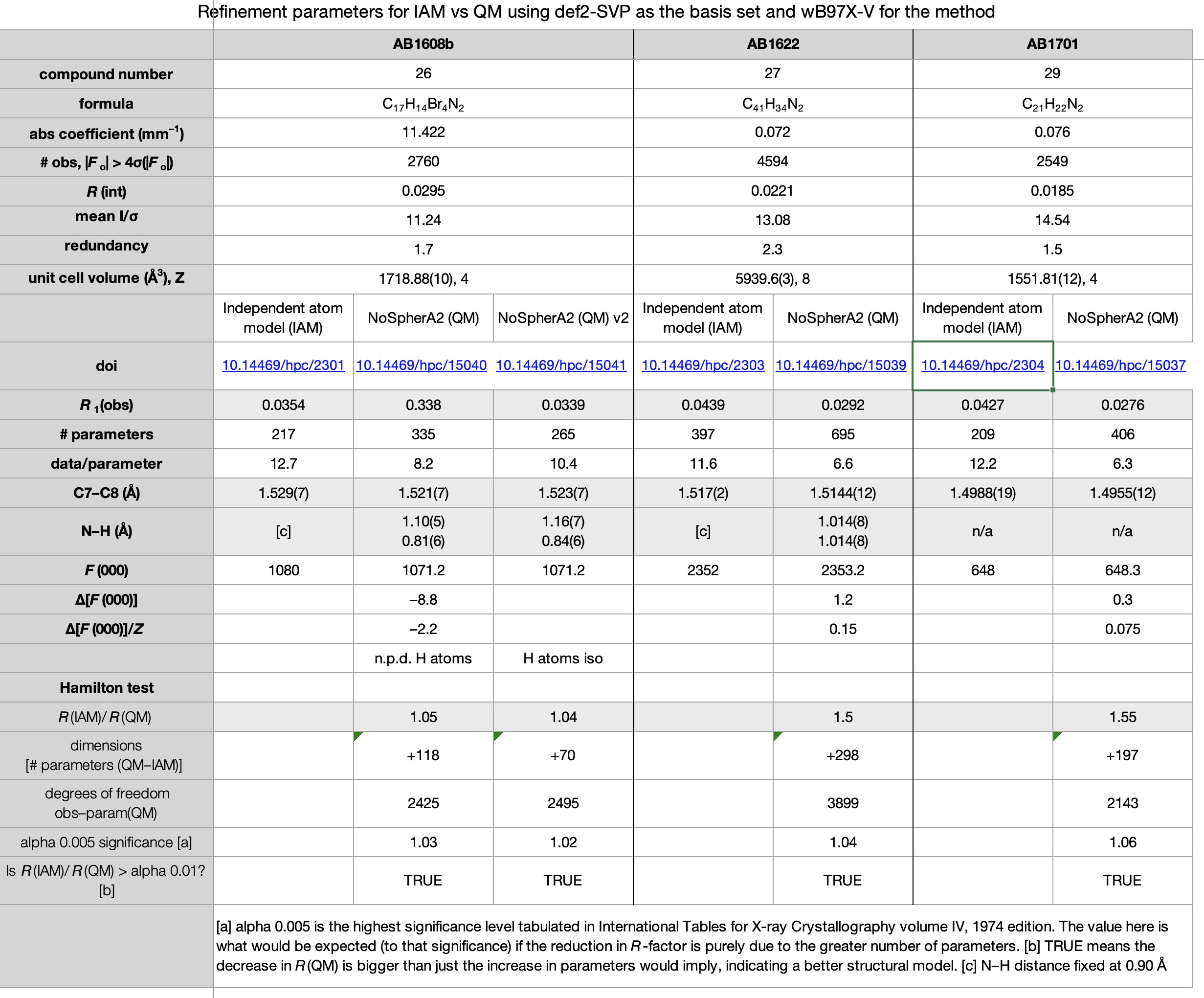

The original published structures[2] were refined with SHELX-2014[3] which uses an independent atom model (IAM) approach. The results reported here employed NoSpherA2[1], [4] using Hirshfeld atom refinement[5] and selecting Def2-SVP as the (all-atom) basis set† and ωB97X-V as the DFT method (the results seem relatively insensitive to either), implemented in the ORCA program.[6] For the first attempts no changes were made to the structures beyond the anisotropic refinement of the now unconstrained hydrogen atoms. For four of the structures a number of the hydrogen atoms went non-positive definite (i.e. one of the radii of a thermal ellipsoid refined to a negative length), which is physically nonsensical and would be a significant barrier to publication. (we don’t quite want to say “unpublishable” as there are almost always exceptions, but a non-positive definite thermal parameter is pretty close to being unacceptable.) For these cases, a second version was created (V2) where all of the hydrogen atoms were refined isotropically but with the distances and thermal parameters still allowed to refine. For AB1709 (18b), this still had the isotropic thermal parameter of one of the hydrogen atoms (H11) go non-positive definite, so for that one hydrogen atom the free isotropic thermal parameter was replaced with a riding one.

The results

We chose a set of seven structures published in 2017[7] and refined as noted above using conventional methods. These seven also comprise one of the very first sets of crystal structures for which full diffraction data were made available,[2] rather than just the refined structure in the form of a CIF file. The new results have also been deposited[8] to augment the record for these compounds. Spreadsheets corresponding to the images below can be obtained by clicking on the image.

- All seven structures saw a reduction in the final R-factor.[8] However, all of the structures also saw a significant increase in the number of parameters (as the hydrogen atoms went from using zero parameters each in a fully riding model to nine parameters each in a fully free anisotropic model). However, all the QM refinements passed the Hamilton test, suggesting that the reduced R-factors do indeed reflect a better model, rather than just being a consequence of the significantly increased number of parameters.

- All four of the structures containing bromine atoms had a number of the hydrogen atoms go non-positive definite when refined anisotropically. It is not clear exactly why this happened – there does not appear to be any correlation with data quality or intensity (as crudely measured by R(int) and mean I/σ respectively), and though the redundancy for these structures is fairly low (between 1.5 and 1.7), those for the non-bromine structures are not much better (1.5, 2.3 and 4.9). These data sets were the result of experiments designed to collect 98.5% of the symmetry unique data with no consideration for redundancy at all. However comparison of the initial and secondary versions of the refinements of these four structure does show that the substantial majority of the observed R-factor decrease can be achieved without using anisotropic hydrogen atoms.

- As regards the precision of the structures, using one C(sp2)–C(sp3) bond as a proxy (the C7–C8 bond) we can see that the estimated standard deviation is either the same or only slightly lower in all seven structures, suggesting that getting lower e.s.d.s would not be a motivating factor for using quantum crystallography.

- One of the more unexpected results was the variation in F(000). In X-ray crystallography (deliberate emphasis on X-ray, as neutron diffraction is different) F(000) is supposed to be the total number of electrons present in the unit cell, and is used as an overall scale factor for the electron density map. It is very much not supposed to be variable, and any discrepancy would indicate an error in the calculated or reported formula and should be corrected. We do not understand why the QM refinements give a different answer than the IAM ones (some up and some down — normalised to a per molecule basis the range is –1.1 to +2.2), though it seems likely to be associated with cut-offs (boundaries) in measuring the “smeared out” electron density in the QM models, The IAM models all give the expected “correct” values.

- Based on the checkCIF reports for the QM structures, if quantum crystallography catches on in a big way, then checkCIF will probably need to be updated, there now being a number of high level alerts for long X–H bonds.

- One of the major areas of uncertainty with quantum crystallography is what/how much data needs to be collected. Symmetry unique data to 0.84 Å seems insufficient, but what would be sufficient — full sphere, redundancy, higher resolution? Would the final results be worth the extra time investment? None of the above aspects are clear at this stage, but it will be interesting to see how the technique develops.

These seven crystal structures also occupy an interesting position for posterity. Data for them has been made available spanning eight years which illustrates two significantly different refinement methods being used during this period, as well as having access to the original complete diffraction image data to allow any completely new analysis to be made in the future. Who knows, maybe in eight years time an even better method may become available for comparison with the results reported here.

‡To put this into context, 0.17 eA-3 would generally be regarded as a pretty low level background noise, similar to the value of the maximum residual electron density a crystallographer might be happy with. †The structure which showed the smallest change in R factor on using quantum crystallography, i.e. AB1608b, was re-run with the triple-ζ Def2-TZVPP basis set. This did give lower R factors but by very little (3.38% to 3.36% aniso with npd; 3.39 to 3.38 iso).

References

- F. Kleemiss, O.V. Dolomanov, M. Bodensteiner, N. Peyerimhoff, L. Midgley, L.J. Bourhis, A. Genoni, L.A. Malaspina, D. Jayatilaka, J.L. Spencer, F. White, B. Grundkötter-Stock, S. Steinhauer, D. Lentz, H. Puschmann, and S. Grabowsky, "Accurate crystal structures and chemical properties from NoSpherA2", Chemical Science, vol. 12, pp. 1675-1692, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0sc05526c

- J. Almond-Thynne, "Crystal structure data for Synthesis and Reactions of Benzannulated Spiroaminals; Tetrahydrospirobiquinolines", 2017. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/2297

- G.M. Sheldrick, "Crystal structure refinement with<i>SHELXL</i>", Acta Crystallographica Section C Structural Chemistry, vol. 71, pp. 3-8, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1107/s2053229614024218

- O.V. Dolomanov, L.J. Bourhis, R.J. Gildea, J.A.K. Howard, and H. Puschmann, "<i>OLEX2</i>: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program", Journal of Applied Crystallography, vol. 42, pp. 339-341, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1107/s0021889808042726

- S.C. Capelli, H. Bürgi, B. Dittrich, S. Grabowsky, and D. Jayatilaka, "Hirshfeld atom refinement", IUCrJ, vol. 1, pp. 361-379, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1107/s2052252514014845

- F. Neese, "The ORCA program system", WIREs Computational Molecular Science, vol. 2, pp. 73-78, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.81

- J. Almond-Thynne, A.J.P. White, A. Polyzos, H.S. Rzepa, P.J. Parsons, and A.G.M. Barrett, "Synthesis and Reactions of Benzannulated Spiroaminals: Tetrahydrospirobiquinolines", ACS Omega, vol. 2, pp. 3241-3249, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.7b00482

- H. Rzepa, "Crystallography meets DFT Quantum modelling", 2025. https://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/15030